Stop what you’re doing

Cause I’m about to ruin

The image and the style that you’re used to

- Humpty Hump

A quick overview of the last two posts:

In Part VI of the series, Matt and I discussed the importance of both intuition (paying attention) and monitoring in the planning a training program. Matt summed it up with 5 practical take-homes:

- A coach who pays attention is the best monitoring tool going

- Data-driven systems are necessary to confirm a coaches’ intuition, and to protect against biases

- Great questions drive a successful data-driven monitoring program

- Effective monitoring systems give you the final few percent in performance - which is what every elite athlete is chasing

- Simple metrics collected consistently over time are extremely valuable, and are often more valuable than sophisticated measurement tools that are unsupported by good questions and difficult to implement

Essentially, a well-constructed monitoring program ensures that we ask the right questions, pick our metrics carefully - and be consistent.

In Part VII, Martin Bingisser described how legendary Russian Coach Dr Anatoliy Bondarchuk incorporates monitoring into his programming. Martin provided five lessons to monitoring from Dr B:

- Measure What Matters

- Measure What You Can Capture

- Measure What You Will Use

- Minimize The Variables

- Don't Overreact

The current post will expand a little on these two - as well as really nicely putting into practice much of what has been discussed in the entirety of the series thus far - from planning, to daily delivery, and everything in between.

I couldn’t think of anyone better to deliver this information than Derek Evely. Derek has a great talent for synthesizing complex issues in a way that makes perfect sense to dummies like me. Derek is also the person responsible for brining Dr Bondarchuk to North America - so has unique insight into his methodology (Dr B lived in Derek’s basement for a year). Much more than being a Dr B clone, Derek - perhaps more than anyone I know - is able to draw on not only his vast coaching experience, but his deep theoretical knowledge gained over the course of his career - especially from his years building content for the Canadian Athletics Coaching Center (which still remains the best on-line resource for T&F coaches - a full decade after its inception). Within this role, Derek pioneered the coaching podcast, and interviewed a vast array of experts in a variety of areas.

He is also an awesome coach. For those who have been reading this blog for a while, you may be familiar with a previous Q&A with Derek back in 2014. And while this post started out in a similar vein (a short question from me, followed by a long, and entertaining rant from Derek), it quickly grew into something far more dynamic. Some of Derek's answers required further discussion, and both myself and Matt Jordan began to dig a little deeper into some of the concepts.

As I said, in this post, my goal was to tease out the application of what we have discussed over the last few posts. The final product is a highly informative and entertaining discussion between two of the best minds in the business (I just tried to get out of the way, and simply allow Matt and Derek to feed off each other).

Normally, I’d break this down into a couple of posts - maybe even 3. But this deserves to go out as one single piece. The length will no doubt scare many people away, and it won’t get as many views as it deserves - but I don’t care. If you don’t have the patience to work through this, then to be honest, you’re not the type of coach this is written for anyway.

Let’s begin with programming, and work from there. We discussed programming and periodization in Parts IV and V of the series. For those who are paying attention, you will know by now that we are proponents of a parallel-complex program for the populations that we work with, as opposed to sequentially-loaded organization. Derek’s programing is very unique. Predominantly influenced by Bondarchuk, he is experienced enough though to have his own take on it - as well as blending Pfaff and Francis principles into the mix.

I hope you enjoy it:

MCMILLAN

One advantage of a ‘parallel’ program is that an athlete reaches peak form much earlier than if they were wave-loading sequentially. In your opinion, is this because of the higher overall quality of the program or a higher density of quality work - or both?

EVELY

I will assume that by ‘quality work’ you mean ‘specific work’. This is an important distinction because most of us can agree that within the realm of ‘quality work’ lies ‘specific work’. However, they are not synonymous. One can perform work that has all the characteristics of ‘quality’, and yet still not be terribly specific - or specific enough. One thing I’ve learned from Bondarchuk’s system of training, is that there are degrees of specificity. I have adopted his exercise classification scheme in all of my writing and methodology because it is such a logical and simple way to classify all of the types of work a coach would give an athlete. It is composed of four exercise classifications, or taxonomies arranged in a hierarchy that goes from specific to general.

The first is the Competitive Exercise. It is the most specific and is made up of loads that mimic precisely the competitive movement and train the same biological systems (e.g. neuro-muscular / energy systems or both). If you are a sprinter, this is the highest intensity sprinting at distances within your realm of transfer. If you are a powerlifter, this is squatting, bench pressing or deadlifting loads in the highest ends of the intensity zones. If you are an endurance athlete, it is runs (or walks) at close to the competitive distance at an intensity that reflects the demands of competition.

Slightly less specific but still very important to the development process is the second classification, Specific Development Exercises. These are loads that honor said intensity zones but resemble the competition movement to a lesser degree (i.e. only in part), or vice-versa. They may include loads that exceed the competition demands. Good examples are high-intensity jumping drills for jumpers or hill sprints / tow sprints for sprinters.

These two rough divisions within the category of specificity are where the most important work we do in developing high performance athletes lies. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to appreciate that the more work you can perform at these levels of specificity, the faster you will improve - assuming a sensible and rational implementation strategy. Parallel, or complex training regimes where all types of work are done in most, if not all, microcycles (and even sessions) offer this advantage.

There is another classification - a controversial one - that some regard as specific while others less so. In Bondarchuk’s taxonomy it is the Specific Preparation Exercises. This zone uses loads that can be unambiguous in their effect on biological systems relative to one’s chosen event but not specific in movement form (although uses the same major muscle groups as the competitive exercise). Weight room exercises are the classic example. Work in this realm can indeed be high ‘quality’, but may not be completely ‘specific’ in terms of one’s event development.

At the lowest end of the specificity continuum lies general work, or in Bondarchuk’s classification scheme, the General Preparation Exercises. These do not follow the competitive event in either their effect on the body’s systems, nor do they resemble it in movement form. While they are crucial for recovery and the maintenance of general fitness, they are not beneficial to creating specific form.

Like most of the world’s best training systems or theories that have stood the test of time, ‘Parallel’, ‘Complex’ or ‘Vertical Integration’ programs that demand regular, year-round employment of the above-mentioned loads evolved as a response to elite coaches searching for ever-better systematic advantages, gradually moving their introduction of specific work earlier and earlier in the training calendar until eventually they realized that it is possible not only to employ specific loads in all periods of the calendar year, but that it is actually an advantage to do so. As well, many believed that this approach offered another advantage; that the parallel development of the key motor abilities created a synergetic enhancement of all others. As one who monitors training on many different variables, I can tell you this is exactly the case.

![]() |

| Bondarchuk Exercise Classification table - as prepared by Tom Crick |

MCMILLAN

So what does this mean? Is it as easy as simply injecting a whole bunch of specific work, as early into the program as possible?

EVELY

Well, not quite. There are two important things to consider - both you allude to in your first question.

First, it is very important to understand that by using this method, you are - in comparison to a sequential-wave loading approach - raising the bar substantially in the amount of intensive work your athletes will perform. It is not inconceivable that depending on how you implement this method you could be tripling, and even quadrupling, the amount of high-quality, specific work introduced to your athletes. Do the math - if you are beginning to throw the discus intensively five times a week in October when your competitors are beginning to throw three times a week in March then you are at an obvious advantage.

I believe that it is not a coincidence that the coaches that pioneered this approach were elite coaches who were not only looking for better methods to develop their athletes, but also had the resources and know-how to provide the quality, daily care for them that is necessary for this method to work.

It has always been my contention that the practice of ‘performance therapy’ evolved symbiotically with the advancement of complex loading schemes because without this form of intervention this system, drug use notwithstanding, is simply not sustainable.

JORDAN:

The question is, why have some sports had such a difficult time adopting this new line of thinking - or are resistant to do so? For example, one argument that has been made in swimming for large volumes of non-specific intensities of swimming is to improve efficiency in the water. You also hear “we need to build a base” in a lot of winter sports, for example. Do you think it’s a matter of old ways of thinking in these sports and that things will change? Or is it highly sport- and context-specific?

EVELY

Well, first of all, athletics (along with weightlifting) has always been the sport that has driven the evolution of training theory and methodology so I think we are ahead in that regard simply for this reason. We focus on very, very specific aspects of human physiological development so naturally we would grow insight before other sports would.

But that only explains some of it. I think a lot of it has to do with being King Shit of Small Hill. The only reason a few of us ever changed in athletics is because others in our sport changed, so we have to follow suit in order to keep up.

Imagine you are a successful coach with a winning record in a sport that is stuck ideologically in the past. You have no reason to change, right? Wouldn't you rather be out drinking and whoring every night rather than exploring new ways to make your athletes better? Sure you would. Unless, that is, you start getting beat. Of course some will come along who possess an ego that allows them to stick their head out of their shell and explore, but they are rare.

I did some work with the Canadian Canoe / Kayak coaches last year, which was a blast. They are asking all the right questions; especially Frédéric Jobin, who is challenging a lot of traditional beliefs in that world. No surprise he coaches world champions.

Perhaps the argument in swimming is correct. It definitely is a unique environment they train in - and one I am not an expert in. But how much is enough? And at what point do you look at it and say "how much is this taking away from the specific work I need to get into the best condition possible?" Hard to imagine that the swimming world is the only one to get away with ignoring one of the fundamental principles in training - the Principle of Specificity.

Remember, in order to fulfill the highest demands of specificity, one must not only be doing the event in movement form (swimming), but must also be stimulating the appropriate physiological systems. We know that transfer in energy system work has wider latitude when it comes to transfer - but for specialist sprint swimmers I wonder if their training regimes are being over-influenced by the endurance events; we see this all the time in the middle distance events in athletics.

It will all change when someone comes along and kicks everyone's ass with a better approach that is not simply "hey, let's throw some speed in all year round" but rather an intelligent implementation of these training ideas we are discussing.

I have no problem with the idea of building a base - I just don't think you need to build one so non-specific and so far removed from the end goal, and at a different time, than the other abilities. Makes no sense to me. And yes, perhaps for endurance sports the latitudes are a bit wider, but I think the principle remains the same. So I think the only thing that is sport or context-specific is how it is implemented.

![]() |

| Derek (with the famous fanny pack), Dr. B and Andrei Abduvaliev |

MCMILLAN

As Derek said - it’s not just winter sports. This kind of thinking has been pervasive in Track & Field for decades. Part of it is simple economy and momentum: in the track world, how do limited numbers of coaches work with large numbers of athletes? You train everyone together for as long as you can. In most programs, this meant that athletes began the year with a general preparation period (cross-country, primarily), and moved towards more specificity over the course of the season (separating into event-groups). The pervasive feeling 50-60 years ago was that all athletes required a large base level of aerobic fitness. Once athletes and coaches have been in this system for a number of years, it is difficult to fight this momentum. It is a fact that most developing systems employ this way of thinking, so that when athletes perform well, they often (as will their coaches) put it down to the efficacy of the system (and not simply the maturation process) - so it becomes more difficult to change tactics. The emotional attachment to a working program is a difficult one to manage.

As an aside - I also think the understanding of training theory is still relatively too immature to expect a paradigm shift in thinking. We are all still just trying to figure this stuff out … What we are taking about when we discuss changing attitudes is progression of scientific theory:

Thomas Kuhn felt that ‘different paradigms cannot be translated into one another or rationally evaluated against one another’ - he felt that once an idea had gone through a paradigm shift, the new idea was not just different - but better. I’m not sure we are there yet with training methodology; sure, we all feel that in our opinions - with the populations we work with, in the culture we live in - that the way we do things is correct (whatever those things are) - but to translate this assumption to a different population, in a different culture, in a different environment, with a different coach is akin to US politicians’ bewilderment at the failure of the Arab Spring: democracy works here - why not in the middle east!?

But the Gestalt shift that Kuhn suggested is not possible. There will always be other supported theories - other sets of principles. There will always be periods of time when competing theories coexist - our job is simply to choose the ones that make most sense to us with the particular population we work with, in this particular time, in our particular environment.

Rather than taking a Kuhnian view on methodology progress, perhaps we would be better served to listen to Imre Lakatos - who suggested that science moves forwards by means of progressive research: a theory is really a series of slightly different theories developed over time - its progression a systematic process that is continually adjusting and developing. Isn’t the fact that there is so much debate and uncertainty in training methodology just the stage in which we currently sit: a natural process of methodological evolution?

JORDAN

I struggle with comparing periodization ‘theory’ to a scientific theory only because I don’t think our scientific community or the practitioners out there are really operating in this type of paradigm. To be considered a scientific theory we would need to be making predictions and testing hypotheses in a robust manner. Instead, I think collectively we just do what we’ve been taught. I sort of see it like a lineage of martial artists … they don’t really test a ‘theory’ of what style works better but actually employ what they’ve been taught, and what they believe works.

MCMILLAN

… agreed - but the question was “why have some sports had such a difficult time adopting this new line of thinking or are resistant to do so?” So why don’t we see cultural change? I am saying it is foolhardy to expect it. If scientific theory change is cumbersome (probably not the right word - but you know what I mean), then how can we expect ‘periodization theory’ to change in any considerable way so quickly? You’re right - and we already allude to it - collectively, we just copy what we have been taught - but there ARE individual exceptions, so in this way, it IS similar to scientific theory: no matter what you call it - whether this be a Kuhnian paradigm shifts, or Lakatos’ progressive research … individuals who do things in a slightly different manner are what drives the change (and history for that matter). Guess I just need to communicate it better

Perhaps a better way of looking at it is through Hegel’s Dialectic:

Rather than seeing the evolution of knowledge as a linear process, Hegel’s Dialectic argued that the initial stages of a theory (the thesis) seem to go well for a while. But the deeper we delve into a theory, the more we find contradictions to it - to the point where eventually, an opposing theory manifests (the antithesis). Finally, we then create a brand-new theory that manages to combine these two seemingly incompatible theories in a unique and practical way (the synthesis).

There is no doubt that many coaches blindly cling to what they are comfortable with. Through comfort, their biases gain strength, and it becomes harder and harder for them to understand alternatives. Like Derek said, the more success that elite athletes and coaches have with parallel programs, the more influence they will yield, and the more we will see this bleed out to other programs, sports, and developmental ages (or - alternatively, the exact opposite!). Through this process, the ‘better practice’ cream will rise to the top, and a synthesis of sorts will appear.

That being said - at this point, it is probably more sensible to place more significance in the people who hold the theories - rather than the theories themselves.

But getting back to the original question in regards to the application of more specific work, and the advantages of a complex system over a parallel system. Derek - you mentioned the importance of increased volume of specific work. I know you agree with Dan Pfaff that density is the key variable that a coach has to control.

EVELY

Yes - density is your tool of choice when implementing a complex approach. Why? Well, when you look at what loading variables you have to manipulate, there isn’t a lot. If you believe - as I do - in the importance of quality loads, then the intensities with which you have to work with are pretty much set (high). From this, it follows that session volumes are dictated by the individual athlete’s ability to repeat efforts in this zone of intensity. So then all you really have left to control is density; the frequency with which you can present such loads to the athlete within a given unit or period of training (session, micro, meso, etc.). Once a coach understands this, the whole idea of constructing micro-cycles takes on a whole new meaning.

JORDAN

This is really interesting and maybe somewhat the basis for flexible prescription of volume or volume ranges? How would you monitor this parameter in a training session to determine when adequate volume has been completed or possibly another way of looking at it is how would you monitor this to prevent too much volume and thus maladaptation?

EVELY

Well, for me this is not such an issue because our session volumes in the weight room are so low that we rarely get there in the first place. However, there are times when I need to drop a set or two on the spot because my eye tells me things are not productive. And then of course, these days I use the accelerometers to back that up. I am not huge technology guy, but that is one piece of equipment that can be really useful.

But this brings up an interesting point for Bondarchuk fans - it is important to keep in mind that in his system you are going to expect some maladaptation in certain athletes. By this, I am talking about the famous ‘three reactions’ that he writes about in his writings. For those that have a natural reaction (to steady, non-wave loaded training loads) that is characteristically down in result before they come up to a peak condition, it is imperative that you do not alter loads to react to that. Otherwise the reaction curve in its entirety will be compromised, and therefore not reliable. You would only alter the loads in a situation where you are sure you have overprescribed, and the loading is in fact too much for them to adapt to no matter how much time you give them.

Because I understand this, and have worked with it and seen athletes respond effectively after a drop in performance, I am sometimes wary of the use of the accelerometers where athletes are constantly kept ‘in the zone’. There needs, for some, to be some maladaptation before there is adaptation. I think this actually falls in line with some things I have heard Dan speak about.

MCMILLAN

This is an extremely interesting area - and where Bondarchuk goes too deep for my simple brain. I remember spending time in Austin in the late 90s marveling at the speeds and times Dan’s sprinters were putting in. And then less than a week later, being totally shocked at how quickly they had seemingly fallen apart. Fly 40 times were up to 1/2 second slower during the latter part of the cycle when compared to the early part (week 3 versus a week 1). This flew straight in the face of what was currently accepted in Canada through the influence of Charlie Francis. In the Francis system - as I understand it - there was very little maladaptation (with few exceptions - most specifically with Issanjenko). He expected an athlete to operate at not only 100% relative intensity, but at 100% absolute intensity. And if the drop-off between absolute and relative intensity was too great, he would plan B the session, or (famously) send the athlete home. Dan, however, not only expected absolute drop-off, but planned his cycles around it (thus the unload week). I’d hesitatingly agree with Derek and Dan that before adaptation, we should expect some performance drop-off (Selye’s GAS being the theory that ‘confirms’ this). What I DO know is that progression is most certainly not linear. The degree of maladaptation is - for me - something that still requires much study, and discussion.

Bondarchuk has studied 1000s of athletes to generate his famous tables (and reaction types), so who am I to question the categorization of reactions into specific types - but I really have trouble with his reducing this to distinct groupings - especially given the population he studied. I’d much rather stick with what we have been discussing - a methodical, intuitive, and reasoned approach that takes advantage of well-designed testing metrics that includes constant and consistent dialogue between coach and athlete.

EVELY

Ok, I’ll bite … first a few important clarifications: I spent a modest amount of time with Charlie and studied his stuff extensively (in fact it has always driven, to some degree, my sprint development protocols). From my understanding, Charlie was very much a believer in the athlete never "being too far away from competitive readiness”. I always understood this to mean that workloads were always of a high quality, NOT necessarily 100%. He believed fundamentally that in order for an athlete to do good productive work they need to be in a state where they can actually benefit from this kind of intensity. To me, that isn’t necessarily 100%; it could be as low as 90-95%, although putting a number on it is meaningless to me (see discussion re: art of coaching vs. objective analysis).

Also, to clarify, I don’t believe Bondarchuk came up with the athlete reactions to training. I remembering asking him about this, and I am sure he said Matveyev came up with them. But Bondarchuk brought them into his theories, and into our thinking. Don’t quote me on all this - but I am confident it was previous Russian study before he brought them to us. Nevertheless, I have seen them at work and they are real. But - and this is huge - they only display themselves when you do not wave-load volume and intensity. Any change within the development cycle and the curve goes all over the place. Below I will provide examples. These are actual curves from Sophie Hitchon, Mark Dry and Sultana Frizzel - I have tons of these I could show you. The curves are repeatable.

![]() |

| Reaction 1: Mark Dry |

![]() |

| Reaction 2: Sophie Hitchon |

Also, it is important to make clear that there are three reactions to a non-wave loaded program application:

- A straight linear improvement (relatively speaking, there are always expected ups and downs in an athlete’s reaction)

- A drop then into a linear improvement

- A flat response followed by a drop in results, then a linear improvement

Most athletes I have ever worked with fall into the first two (see curves above - I have no examples of a reaction 3 - they are rare, and I have yet to coach one).

I have recently been talking to Mike Tuscherer - who is experimenting with this system. He is getting solid and reliable curves as well - as reliable and pure a curve as I have seen - in a different sport, with different parameters; same with Nick Garcia in LA - near-perfect curves most of the time. So there is definitely something to the curves and the reactions. What a coach does with them is up to them. Worth studying though in my opinion. I mean shit - what Bondarchuk is saying here is that when you do not wave-load volume and intensity you can expect a reliable, consistent reaction to loading. Is that not what we wish for in periodization and planning?

But to respond to your comments directly, I think it completely depends upon your system of training. In ours (Bondarchuk), you want to expect, with athletes in the second two reactions, that there is a predictable drop in form prior to a linear rise. But if you look at his literature carefully you will see that the drop is not less than 5% of the initial form - not all that much at all. We are not talking here about a complete crash so one could argue it still falls within this idea of “quality loads”.

MCMILLAN

Very interesting - and not something I am well-versed in at all. I must say I am somewhat surprised that an athlete’s adaptation response ‘type’ would remain constant over time … this requires another blog-post in itself …

EVELY

They don't remain constant over time in my experience. I have found that athletes will display types one or two, depending upon the program prescribed. The time to reach peak condition will also change in my experience - but usually that is simply a reflection of an athlete's experience with the system and their level of development.

For instance, when Sophie Hitchon started with me in early 2010 she was consistently a reaction 2 and took 45-50 sessions to reach peak condition. By 2012 that had evolved to a type 1 reaction and 34-36 sessions to reach PC. She was very reliable in this regard.

Like I said - I have seen it over and over. It is repeatable - no doubt.

But, getting back to your question regarding density - the more systematic and regular the exposure to intensive, specific loads, the faster an athlete will improve over a given time frame. But - and this is critical - an athlete can only execute a finite amount of this type of work at any one time - beyond which it no longer can be called ‘quality’ work. Therefore, successful implementation of highly regular, decidedly specific loads is extremely dependent upon the interplay of these two realities. It is a balancing act; you want to set up quality sessions that optimally tap into specific resources (thereby leading to adaptation) and do it as densely as possible - all the while respecting the fact that if the spacing of the loads is too dense it will negatively affect the quality of the individual sessions.

JORDAN

OK - so that brings up a question: suppose a young, or inexperienced coach adopts this method and pushes a little too hard - and they end up prescribing too much density of specific work. How would they notice a problem has arisen? What is the remedy? Is it time off? Reduction of density? Reduction in overall load?

EVELY

They - and you - will notice there is a problem when unexpected and/or prolonged drops in specific measurables show up in your monitoring. As discussed, some systems will actually plan for a drop in measurables (e.g. Verkhoshansky’s Block or Bondarchuk’s system), however these are predictable and happen in the context of the load-delivery system (methodology) being used. In Bondarchuk’s case they will not be prolonged.

The remedies for overload problems are very situation-specific. It depends, in my opinion, upon how reliable your loading has been in the context of the specific session. For instance, if you are loading the athlete with sessions that are in some fashion familiar to the athlete (i.e. you have seen them react well previously to the session load, framework, etc.) but you have simply pushed the envelope in terms of density because you are running out of time (e.g. competition in the horizon) then the answer is self-evident; ease the density. Relieving the daily, or session, load in this case may send them into an early, ineffective peak condition - or none at all. While this is a better mistake, of course, than ignoring the problem, adjusting the density may get you out of the situation unscarred.

However, if you were simply experimenting with different load-intensities in sessions designated for specific work, and it clearly is too much for the athlete as witnessed by your observations (acute neuro-muscular fatigue, breakdown in mechanics, etc.) then you must pull back on the session load. Otherwise they may not only drop in measurables but they will get hurt.

Therapeutic inputs should also be a constant - and of course this is another tool with which you can use to manipulate the effect a given load has on an athlete’s reaction to training. I look at therapy the same as other training stimuli; add more, there will be a reaction. Take it away - another reaction. It does not exist independently of other essentials in the training process.

Lastly, one is well advised to remember that the day-to-day measure of success here is not simply a question of load tolerance or survival, but rather one of enhancement and growth of an athlete’s form over the medium- to long-term. Therefore, the parallel, complex or VI approach must be employed with all eyes on, all the time. It is not for coaches who are not prepared to be present daily - both physically and mentally.

JORDAN

I have to say, if there was ever an argument that knowing what matters, tracking what matters and showing what matters is moving in the right direction, I think this would be it!

Do you think the complex - parallel approach is something that only fits for certain sports?

EVELY

Hard to say with absolute certainty. But to me, physiology is physiology, so at the very least it should work as well as any other perspective. Whether or not it is better than a stage approach for endurance sports, for instance, is for coaches to experiment with.

And remember, successful implementation of the VI / Complex / Parallel approach is a matter of degrees. You can blend approaches. For example, you can set up all of your yearly cycles so that the development of all exercise classifications is present in all - but concentration is shifted toward one or two abilities more than others. Even the Bondarchuk system allows for this if you want to set it up that way.

MCMILLAN

Derek - you have mentioned now a couple of times specifically about NOT wave-loading volume and intensity. When I first came to understand Bondarchuk’s programming, this was very eye-opening (and initially surprising) to me. Can you expand on this for coaches who may not have been exposed to the actual application of the principles?

EVELY

While it is a characteristic of all top-notch programs that loading is consistently high year-round and the waves or volume & intensity are kept small, we take it a step further. Once a ‘program’ (a workout or single unit of training) is prescribed and given to an athlete, it is simply repeated over and over again without change until an adaptation response is observed - leading ultimately to a peak condition. There may be more than one program (workout - training unit) presented (I usually employ 2 or 3) but once initiated they do not change until a peak condition is reached. We change the exercises only when a peak condition is reached or a peak condition needs to be maintained.

Those who are familiar with Dan Pfaff’s roll-over competitive cycle understand what I am describing: two to three sessions that are repeated, in order, over and over. Only the density of the sessions is manipulated. The difference being is we use that scheme all year round in all cycles.

Think Chinese water torture: sessions are the drops: drip, drip, drip ... You change the drops when adaptation occurs.

See the example programs below. Each program is a ‘drop’. There are three different drops in this cycle. This particular set of programs went for eight drops each, in order, for a total of 24 drops or sessions at which point peak condition was reached. The session before the competition was a modified session '1' as it was a pre-comp stimulation session.

MCMILLAN

Another unique part of Bondarchuk’s system is the relative lack of importance he places on traditional maximum strength development. In your opinion, how important is intensity (as a product of RM) in weight training? Is it as simple as reaching a point of diminishing returns? i.e. the weaker-younger-less experienced athletes require more work on maximum strength, while the stronger, older, more experienced athletes require less of it - and more specific strength work instead?

EVELY

In some ways working with high performance athletes is less challenging than trying to put together a truly appropriate, productive long term development plan for athletes who may be gifted. The reason for this is that in terms of preparing an athlete for a high performance career, it takes a lot of time before you realize the real fruits of your efforts. If you screw up, you won’t know until 8-10 years down the road.

JORDAN

What helps in this instance to know if you’re on track? Do you track performance over time and have an idea of the bandwidth in progression so that you know you’re in the ball park?

EVELY

Tough question. Not sure if there are reliable measures to monitor this. Of course there are objective standards we can research from past elite performers, but even those can be misleading. However, I consider a development coach successful based upon three criteria:

- They produce results consistently

- The athletes that come out of their program are coachable. By that I mean they have not been successful as the result of maximal exploitation of specialized loads. They have a strong base of strength, solid mechanical foundation, and their speed or endurance abilities have not been compromised. In short, they are ready to rock

- Health history of the program is good. Athletes graduate bulletproofed. Robust, healthy and ready for a high performance coach to load with the appropriate level of training. Results are meaningless if there is a trail left behind of crippled athletes. Likewise, a high performance coach should not have to spend 2 years dealing with health issues before they can initiate high performance training.

There is a fourth criterion worthy of mention - and that is the legacy left by the coach for the sport. By this I mean the quality of people that graduate from their program that go one to make a difference in the sport. By this I mean future coaches, supporters, leaders, etc.

But having said this, I think many obsess over details too much when it comes to the strength programs of developmental athletes. To me, it is more about what you don’t do rather than what you do. Sure, there are some important and useful strategies that will ensure balance and the proper development and preservation of speed qualities - and those indeed should be planned for to some degree - but a talented athlete in a healthy high school sport environment is already halfway there. Coaches for developmental athletes need to keep their eyes focused on the end-game when designing their long-term plans (assuming they are actually doing this - in itself a big assumption) rather than trying to include elements that will produce results in the short term. Some get away with such exploitation. Most don’t. And next to the too-early introduction of specialized workloads in endurance running and sprinting, specialist intensification in the weight room is the numero uno culprit in this regard. My approach with younger athletes has always been that if I err by being too cautious with the lifting intensity, then they can always catch up later - get the basic speed and mechanics right; it is far harder to catch up in any motor ability later on if speed qualities are compromised during key periods of development.

JORDAN

This is great - do you have any universal approaches for assessing this? In some circles, I suspect they might suggest a FMS screen would be the way to evaluate the athlete at this age. Of course, I’m not advocating this but I guess what you wrote here opens the door for fluffy, ineffective training. You might see coaches saying - “let’s forget about intensity, and focus on low-load motor control drills instead.” How do you differentiate between the two ends of the spectrum - i.e. over-prescription of intensity vs. over-prescription of fluffness? Any thoughts on how you assess an athlete’s readiness?

EVELY

Good question. I suppose the phrase "preservation of speed qualities" is a poor choice on my part because working with development athletes is about - well - development; not preservation. But when I started using that phrase it was an over-reaction to the carnage I witnessed on tracks all around me. A better phrase might be "preservation of the integrity of the neuro-muscular system”, but that is a mouthful, and makes me sound way smarter than I am.

But you get my point I think. And you are so right; going too far the other way (fluffy loads) is not ideal either - although it is a slightly better mistake than over-intensifying too early. The most successful development athletes I ever coached worked as hard as any athletes I have ever worked with. They just did it in a way that enhanced their long-term objectives rather than detracted from them.

But a half-decent coach with a good work ethic should be able to find the middle ground fairly easily I believe. It's not rocket-science - all that is needed is a bit of research and good planning.

Here is what I tell coaches whenever I speak on this issue: don't confuse specificity with specialization, they are not the same thing. Developing athletes can be specific and be specific regularly. If you are a young pole vaulter you can pole vault! But what you need to watch out for is specializing too early, or intensifying training before you are prepared for it.

Being specific to me in this context is simply doing the event: sprinting if you are a sprinter; throwing if you are a thrower; playing water polo if you are a water polo player. This they can do until the cows come home - generally speaking. But specialization is a whole different ball game. That means not only focusing on one sport or event, but also digging under rocks to search out and maximally exploit all of the separate abilities needed to excel in a given event. This type of pursuit drains resources to the point where only well-prepared athletes can tolerate it over the long-term, and even then, they eventually tire - either physically or psychologically - to the demands placed on them. The general rule is 8-10 years of this either way. Start it too early, and eventually you have drained your well at a time when your competitors are still able to find reserves. Start too late (or with too little preparation) and you narrow the time-frame with which you have to specialize.

Nonetheless, attention to intensity is critical when working with elite and developmental groups - and everything in between. I think many underestimate the effect high intensity lifting has on the athlete’s overall system when you are running parallel or complex programs. For athletes who are doing regular dosages of highly specific work the poorly planned inclusion of intensive lifting loads can disrupt everything from day to day recovery to the development of mechanics in technical work. If you are running a parallel regime and your goal is to get away with as dense a program as you productively can, then this is surely a critical element to monitor. Next to the first two categories of specificity I previously mentioned, this is next in line when it comes to studying the effect it has on training. Properly implemented, it is your best friend. Poorly implemented, it is your worst enemy.

This illustrates the complexities when one is implementing a parallel methodology; if you overload session lifting volumes or intensities, it has a ripple effect with the development of other abilities that needs to be immediately dealt with. Screw this up in a stage system and you simply give more recovery; the only real point of danger in this approach is the point in the period where volumes are on the decrease and intensities are rising. This is where load is highest, and people get hurt. But even still, you have the advantage of seeing this coming a mile away. In a complex system you don't have this luxury - you must be monitoring all the time.

![]() |

| Jeremy Wotherspoon - skating at the 2010 Olympic Games. Photo: Reuters |

JORDAN

I would say this is also true for endurance sports that require considerable upper body and lower body strength. I’m thinking of speed skating and cross country skiing - but in general, it’s the same story … the inclusion of too high an intensity of strength training can completely disrupt adaptation to specific loads.

EVELY

Yes, but if that is the plan, and it is accounted for in the planning process, then perhaps it is a rational approach. For instance, you may have a cycle planned where you are going to push the envelope a bit in the strength direction while still performing highly specific workloads. For a short-term this may work as long as a) the timelines fit in with your overall planning strategy and b) allowances are made in other areas to accommodate that extra strength load (e.g. specific workloads reduced). But often these allowances are not made; that is, the coach, or whoever is prescribing the load, compartmentalizes the different forms of work in their heads, as if each form of work drains a different and separate bank of reserves within the body.

One of the reasons this whole concept of parallel loads is so hard to get across to people is because people think so black and white. In terms of the implementation of strength loads, this equates to either you slam them with specific strength loads, or you don’t include them at all. But coaches using a complex methodology - successfully - know that effective dosage prescriptions are far more subtle and refined than that. This is where the art of coaching comes in; like a painter working on a painting - a splash of red here, a splash of blue there.

Interesting you bring up speed skating. I am currently working with a girl who is a short-track speed skater making the move to long track because of concussive injury. It is an interesting case, because her story and the solution (as I see it) to her problems include some of the issues we are discussing here. Currently, she cannot tolerate dense, intensive loads, but of course still needs to do specific work to be successful. My approach has been to remove all but the most specific forms of work on ice using limited volumes and full recoveries. In addition - to keep things simple, and so that I can keep a handle on monitoring things - I included no formal strength or special exercise for now - nothing but her specific skating loads and some upper body general strength and aerobic work. In effect, a very polarized regime. From what they tell me this is a very foreign concept in speed skating.

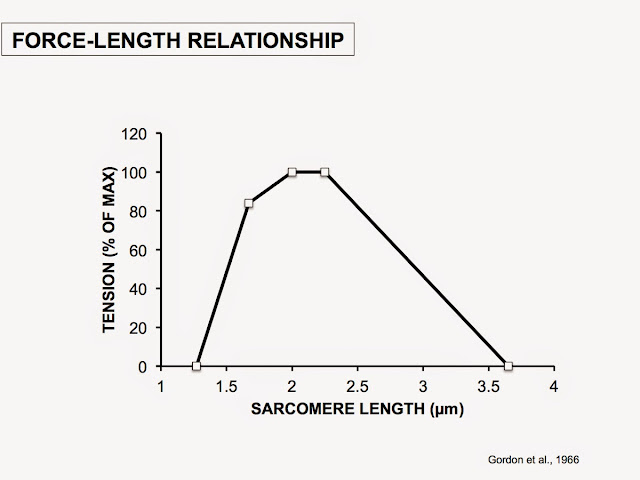

So here is a question for you Matt, as you are so familiar with training speed skaters: in athletics, the time under tension during force-application for - say the ground contact times for a sprinter or the take-off of a long jumper - is relatively short and ballistic in nature. In speed skating, the phases of force application seem much more isometric in nature. Also - the joint angles - especially at the hip and knee - seem to be much more acute than what we deal with in athletics. When I introduce some forms of specific strength training for this girl (which I will next year), how would your approach differ from what Stu or I would do in athletics for say a sprinter who has, generally speaking, milder angles and shorter ground contact times?

JORDAN

That’s a great question. Interestingly, and a bit of an aside, we regularly find that squat jump performance is better than countermovement jump performance in sprint speed skaters. I’ve seen this for years and I also find this regularly in elite alpine ski racers.

Now, it is often assumed that this is a consequence of poor reactive strength or a deficit in their ability to use elastic energy, but this argument never made sense to me. After delving into some of the jumping simulation studies, it seems that storage and release of elastic energy plays a very small part in countermovement jumping (read Maarten Bobbert’s work), which makes sense as the descent primarily stretches the patellar tendon and gluteus maximums tendon, which are relatively stiff and do not store elastic energy as their primary function is to transfer forces between joint segments. Simulation studies indicate that the primary difference between a countermovement jump and squat jump is the development of a higher muscle active state as a result of the rapid countermovement versus the squat jump, which starts from a static posture.

MCMILLAN

Matt - this reminds me a little of Bosch’ theory that ‘co-contraction’ is a more efficient manner from which to produce force than counter-movement. If I understand him correctly, he argues that creating pre-tension (and stiffness about a joint) via co-contractions is a more effective strategy to apply force than the relatively more costly counter-movement. How I read it, the weaker, less efficient, person will spend more time - for example - on the ground in preparation to jump for a rebound (greater amortization, greater yielding angles, etc.) than a more efficient athlete (who presumably is more efficient with a co-contraction strategy, and will spend less time yielding, and therefore jump earlier/more powerfully (think Dennis Rodman - or from a sprints perspective, the faster sprinters perhaps spend less time on the ground as a result of greater - more efficient - co-contractions). I know when we used to test vertical jumps and counter-movement jumps back in the day with the athletes in Calgary, jump squat was definitely a better performance predictor. Now whether this was-is due to better ‘co-contraction’ or not is a discussion for another day.

JORDAN

That’s an interesting point of view and I’m not sure I can answer without putting a lot of thought into it. In general, I guess the question is: what’s the goal? From an energetics standpoint, it would be more costly to have large amounts of muscle activation - or co-contraction, and thus a countermovement might be perceived as more efficient at least if it was like some sort of bouncing gait like long distance running. I would also think that pre-activation plays heavily into the picture - namely the ability for preparatory muscle activity prior to touchdown to limit force leaks and ensure all the ‘slack’ is taken out of the system. In general, it seems athletes with a closer ratio of CMJ:SQJ heights are our stronger athletes, who are better able to produce high rates of force development with load. Maybe this goes along with the idea of being able to generate a higher muscle active state and thus more work in shorter period of time (i.e. greater muscle power). I have to be honest, here: lots of speculation happening on my end!

MCMILLAN

This discussion reminds me of a few conversations I have had with Jeremy Wotherspoon over the last few years. I received an email question from him last week that I hope you guys can share your thoughts on.

Matt - we know Jeremy well, having both worked with him in the past. For those who are not familiar - Jeremy is now a speed skating coach in Norway. Before he became a coach, he was almost certainly the best sprint speed skater of all time, and has some excellent insight into training, mechanics, race preparation, etc. I am certain he will be a wonderful coach (he is already producing some excellent results). Anyway - his question is this:

JEREMY

Had an interesting idea yesterday - "maybe it's better to learn skating technique when you are relatively weak - too weak to overcome technical flaws with brute force or muscling your way into the ice." I'm pretty sure that's how I learned to skate well, the only strength training I had done before I got "good" at skating was skating for 9 years, and other sports, no off ice training for skating, weights or otherwise. I had to hit the timing and position right so any force I could produce went into the ice, had to wait until I was "standing" and feeling a little isometrically or isokinetically? loaded on the blade about to be used before pushing.

JORDAN

Leave it to the world’s greatest sprint speed skater turned coach to come up with a really interesting thought! I have to be honest - I never considered this. It sure goes against intuition that getting stronger can only help an athlete perform in sprint events. Nevertheless, it seems like this is a common thought amongst long-term athlete development proponents. I’m really not a fan of LTAD for a variety of reasons but I’ve often heard comments to the effect that athletes who develop more slowly need to rely on technical competence, whereas early developers get away with technical flaws at a young age due to superior strength. The thought seems to be that this plays out in the senior ranks with those early developers lagging behind due to faulty technical patterns that are nearly impossible to change.

Over the years as I was hanging around the Olympic Oval, I also remarked on how the Asian countries who were at the Oval for training camps with really young athletes would spend inordinate amounts of time doing basic drills emphasizing deep knee angles (not in the weight room!). Contrast this with the Canadian system that tended to hire strength coaches and to push developing athletes into doing the fancier stuff with the aim of producing a faster skater. In the end, there really didn’t seem to be any debate that many of the Canadians really lacked in the technique department compared to their Asian counterparts.

Another caution is that a good example doesn’t necessarily make a good argument. Although it’s compelling, it’s tough to think of all the factors that would have helped Jeremy succeed the way he did. He was also very lanky relative to other skaters and he definitely had a gift for explosive strength - not to mention a very cool calm and collected demeanor on race day. He was incredibly gifted in a number of areas, but not doubt, he had excellent technique.

Maybe the question comes back to the importance of emphasizing elite-level technical competence earlier than we do in some sports. Other than sports like gymnastics or figure skating, I get the feeling there is a tendency to be more lenient on technical proficiency with youngsters. We emphasize fun and then at some point we seem to go from fun to hiring strength coaches (at least this is what I see in a sport like ice hockey in Canada with big participation numbers). Kids go from skating how they skate, shooting how they shoot, making the team they make, to parents calling me up when the kids are 12 asking me to pull out an agility ladder and make their “feet fast”, and to see if we can fit this in around their treadmill skating work where some 18 year old jacks up the treadmill and skates him till he pukes.

Here’s the clincher - what I’m describing above seems to arise as well in logical periodization approaches - which recommends for athletes to move from general to specific. If Jeremy is onto something we would be saying get specific early with technical competency to maximize the specific adaptations that are needed for future level elite performance. Once this is there, then we add general elements like maximal strength and explosive strength, etc.

It sounds like we are saying to eliminate ‘windows of specialization’, ‘build your aerobic base first’ and use ‘linear periodization schemes’, and instead to prioritize the specific technical demands of the sport first, followed by the right amount of general training elements to support the individual needs of the athlete. Yes - this sounds right to me and far superior to what is taught in the text books.

EVELY

Very intriguing question, and one that is quite pertinent to our discussion. In fact, in reading this I realized that in our discussion on early-specialization I forgot to mention the cardinal rule in youth development: mechanics and speed first. Strength has its place, but like our discussion around strength implementation with high performance athletes, it cannot negatively influence the development of these critical elements, because it is simply too hard to catch up in these specific abilities if they are not rooted firmly in an athlete’s development. It can be done, but it requires exceptional skill on the part of the high performance coach, and even then the athlete doesn't reach their full potential half the time. Don't get me wrong; both speed and mechanics can be developed all throughout an athlete’s career - but why not make everyone’s life easier and prepare an athlete to be sound in these all-important abilities, so that when they progress into a serious high performance setting they are ready to incorporate the more specialized workloads and thrive off them?

Ask any high performance coach which athlete they would rather take on: a “weak” but fast, mechanically principled athlete, or someone with mediocre skills but can (in Dan’s words) “lift the weight room”? No contest every time. A high performance coach has nowhere to go with the second one. I’ll bet even endurance coaches would rather have the former rather than the latter.

Sometimes I think that the worst thing a young athlete can do is display their talent. I say this because this is often the moment when everyone around the kid begins to go batshit crazy and all of a sudden everyone is an ‘expert’. Everyone around starts licking their chops and planning the kid’s future - when in fact all the kid needs is to be left alone with his or her coach.

So I read Jeremy’s question and think he is a great example of when we actually get it ‘right’ … ironically it is not because there was some kind of systematic LTAD model in effect but rather it was simply because nobody ever got in the way. In athletics 90% of our successful athletes come to us this way. I am a fan of LTAD, but I think we need to look at examples like this and take notice - they are not flukes; they are telling us something.

![]() |

| Jeremy is now coaching in Norway |

JORDAN

Derek - to speak to your initial question: my hunch is elite speed skaters might be highly adept at generating a high muscle active state and thus are able to perform as well if not better than in a countermovement jump. This makes sense based on the type of training they do and the specific adaptations that you would imagine occurring if an athlete was to spend considerable time in a low position.

We also regularly see that elite level speed skaters can generate this active state from deep knee angles right around 90 degrees of knee flexion, whereas less developed speed skaters choose to sit at smaller angles of knee flexion - assumedly because they are generally weaker, and looking to stay at joint angles that are less taxing.

I think what we can surmise from these two observations is that elite speed skaters have adapted their lower limb strength curves for the plateau region to be around 90 degrees of knee flexion and that being able to generate high levels of activation from this position is a key for putting a large impulse into the ice. As another aside, I have had a few conversations with Andy O’Brien (strength coach and sport science lead for the Pittsburgh Penguins) and he also seems to find this type of thing in the best skaters in the NHL.

A roundabout way to get to my point - but I think there might be something in these two observations that can lend credibility to what I’m about to say. The first distinction is that I do a ton of single-leg work with speed skaters and I emphasize movements that develop strength just below and in and around 90 degrees of knee flexion. This means taking single-leg squatting exercises down below 90 degrees and being creative with isometric and eccentric loading conditions around this joint angle. Another thought is to focus a lot of the Zone 1 type loading from this knee angle, and again - I prefer single-leg variants here as well. Note that to avoid interference, I tend to switch to double-leg loading and higher angles of knee flexion if the volume of on-ice specific training is high. Throughout all of this training, I tend to emphasize the idea of generating an early and high muscle active state from these low positions - to evaluate that we are getting the adaptations we want, I definitely make use of feedback (e.g. linear encoder or an accelerometer like the Push Band) to provide feedback and ensure the athletes are giving a maximal effort.

JORDAN

Derek - I’d like to go back to loading again, if you don’t mind. As I stated, the inclusion of too high an intensity of strength training can disrupt the adaptation to specific loads - which begs the question

“what about concentrated or block loading?”

My understanding from personal communication with Verkhoshansky is that this is the very reason for abandoning parallel-complex, and moving towards block style training. Any thoughts on this?

EVELY

Great question. I think I partially answered this earlier - it is a matter of degrees. Many call the Bondarchuk system ‘Block Loading’ or ‘Block Periodization’, but if you look at what he actually does in his coaching, it is the farthest thing from that if your definition of “block” is in line with Verkhoshanky. In Bondarchuk’s writings he does, of course, discuss the block method, but it is simply one of the many methods he describes. In practice he almost always uses some form of a complex methodology.

But, that does not preclude him or anyone else using his methodology, from emphasizing the development of a certain ability in any given division of training.

For example, the key cycle in Bondarchuk’s system of training is the ‘Development Cycle’ (the formal name is the Period of Development of Sport Form, or PDSF). This is somewhat akin to a meso or macro, depending upon how you define it; it is a collection of microcycles. Depending on the athlete you may get 5-7 PDSFs in a given year - some athletes more - some less. Those cycles (at least in the way I do it, and have seen Bondarchuk do it) are always complex, parallel or VI in nature (for argument’s sake let’s call these synonymous). There is nothing stopping someone using this system to prescribe say an early season PDSF with an emphasis on say the Specific Preparation Exercises or a mid season PDSF with an emphasis on Specific Development Exercises. But to be successful, in my opinion, one will have to abide by the general principles we have been discussing. For instance, the emphasis cannot be so embellished that it drastically affects the specific workloads for extended periods of time.

Bottom line with the idea of block training the way Verkhoshansky envisions it is this: I have discussed this with many elite speed / power coaches and none of them - without exception - can fathom large blocks of training without technical or highly specific workloads in them. I doubt they are all wrong. This in itself should tell you something. But this doesn’t make the concept obsolete or irrelevant - it simply means that we need to take the relevant ideas within Verkhoshansky’s concept and adapt it to our own prerequisites. This is something coaches should be doing anyway; blind faith in any one system will only lead to disaster.

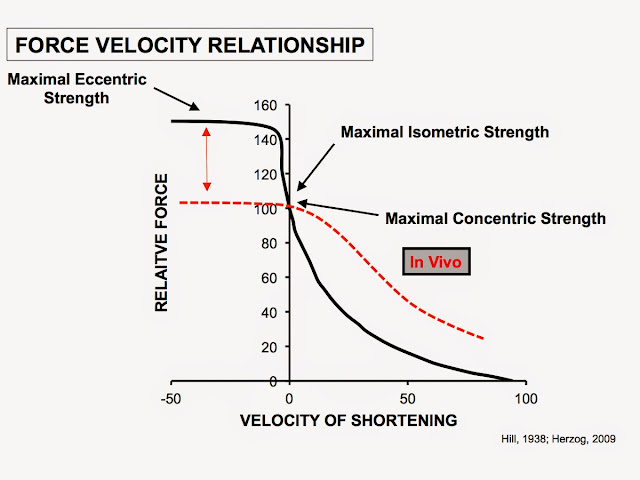

Generally speaking, I think that when you are designing a long-term development plan for athletes with potential, you want to systematically include work from all zones of the force-velocity curve, including parts of the higher end of the curve progressively as they get older and more developed. However, when dealing with elite athletes, there needs to be a far more individualized and surgical approach.

JORDAN

This is an interesting point - it’s interesting to note that the scientific literature seems to lag behind this practice. In my opinion, I still think the dominant viewpoint in the scientific community is that heavy loads are far superior for pushing adaptation across the entire FV curve. I’m not saying I agree with this by the way. I guess the question is whether or not the scientific opinion is correct in that the primary loading zone bringing about adaptations of interest is Zone 3 (max strength) and that the athletes progress largely despite the lack of Zone 1 work (dynamic strength). Or, is it a critical part of the loading continuum? I go with the latter - we just need to show it’s the case

Put another way, I guess I am asking whether or not zone 1 training has an effect in addition to the zone 3 training in terms of the adaption. Or is it really the zone 3 loading that elicits adaption and the zone 1 training is really trivial. So it isn't because of the zone 1 training that adaptation occurs but instead, adaption happens despite its inclusion (I.e. doesn't make them any worse but doesn't make them any better)

I say this because there isn't a lot of data in the scientific literature showing an effect of zone 1 on maximum strength and a lot of strength purists think it's bunk. Yet, the three of us have plenty of examples of it working.

I guess I am fishing for case study examples where it's worked for you and because you have data on this it makes it more credible.

EVELY

First of all, I absolutely agree that maximum strength loads push adaptation across the F-V curve and that for those looking purely for strength adaptation along the curve this is perhaps the best approach. However, I am simply not convinced it is a superior strategy in the context of transfer to the event I coach, which has, arguably, the most to benefit from maximum strength training than any other athletics event. Does maximum strength transfer to throwing? Sure it does: even Bondarchuk’s research indicates that. But his research also indicates that the transfer from maximum strength lifting is minimal relative to specific exercises for high-end athletes, and this is where the rubber meets the road for us (note: more transfer is observed the farther down the scale you go, from elite to sub-elite athletes).

So then the issue becomes, how much transfer does one get from a given exercise? Because our athletes have - like all other athletes - only a finite reserve of energy to put into training we have to think like economists to get the biggest bang for our buck. We have to choose exercises and loads that we know, or suspect, have the highest transfer. This comes from our observations, experiences and data. Number one on this list is of course, the most specific types of work. For Stu that is sprinting; for me (these days) it is throwing. Next is specific strength loads and special exercises (SDE in Bondarchuk’s classification). After that comes the classification that includes weight room work. It has its place - just not as high up the ladder as others place it.

So then the next question becomes “where does maximum strength work fit in to ‘weight room work’ and why should we be so cautious with it?” I mean, what’s the big deal?

Well, maximum strength training is notorious in athletics circles for causing injuries and draining the neural bank. The injury point is self-evident, but can be dealt with with proper preparation and instruction. The neural bank issue is tied to all kinds of other complications such as interference in motor learning, depletion of specific energy reserves, etc.

So if we accept the notion that a certain level of maximum strength is necessary then the logical question becomes “is there a way we can get it and still avoid the pitfalls of maximum strength work?”

I believe there is, and this brings us to your initial question:

I accept that there may little evidence to support that zone 1 training leads to an improvement in maximum strength. However, I have seen too many examples of adaptation the other way. Now, the examples I have witnessed have all been with very high-end athletes, so one could argue there is a certain amount of neuro-muscular aptitude for such an effect to exist (remember, most studies in these areas are done with ‘normals’).

I am not saying here that someone who sprints regularly is going to go out and break the world record in the deadlift - but I do think there is a transfer there and it is significant enough that guys like Stu and I who are always searching for the most economical ways to do things need to pay attention to it. We think in terms of the ‘minimal effective dose’ as has been mentioned often in ALTIS circles.

Now for me - working with throwers - zone 1 is where we live: speed-strength, power, and at times strength-speed. I can absolutely tell you with a high degree of certainty that training in this zone will drive your maximum strength levels. I have seen many examples of this, but I will offer two here:

The first was last year - in May - while working with hammer thrower Sultana Frizell. She had not squatted either heavy or deep in almost 10 years. Yet within a workout or two of the introduction of low volume, high intensity squats she was squatting loads well above the research data I had on necessary strength levels for female hammer throwers (which I received from Bondarchuk). I actually never let her get completely into the lower velocity range for fear of injury. She told me later that the loads she was pushing rivaled - if not exceeded - the loads she was using back when she was squatting heavy 10 years prior. (more on this later on - SM)

The second anecdote involves Dylan Armstrong, and is even more illustrative.

One day years after I had left the Kamloops program - I think around 2007 - I got a call out of the blue from Dylan.

“what’s up?”

“you won’t believe what I just did…”

As I have mentioned, when Dr. B took over Dylan’s program he immediately removed all of the heavy loads we were using in the weight room. By 2007 he was having Dylan stay consistently in what I can only guess was the 65-70% or lower intensity range in his lifting. I say I can only guess because there was never any 1RM testing - loads were simply chosen at random, based upon Dr. B’s eye and experience. But there was A LOT of special exercises involving the shot put arm-strike movement; everything was fast, fast, fast … push ups, weighted dips, special throws, bench - whatever he could dream up. Mostly zone 1 and some zone 2 work.

So one cycle he has Dylan doing dynamic bench, using around 135k - fast - 5 reps or so. Dr. B walks in to weight room and on a whim says “let’s see what you can bench”. Dylan starts loading the bar and stops after he benches 510 for 6. That’s when I got the call. He was stunned because he had not done any maximum strength work in years. That result was approximately a 100lb increase in his best bench result from when I coached him.

So I ask you - why lift heavy???

MCMILLAN

Well - you hit the nail on the head a couple of times, when you mention athlete level, and study subjects. The fact is the lower the level of athlete, the more they will require some sort of maximum strength work - and lets face it, 99% of all strength studies are done on sub-elite athletes (and oftentimes not even that) - so of course the studies are going to point to the efficacy of this type of loading. We discussed previously about reaching a point of diminishing returns on various abilities - it is no different with maximum strength.

So you do not do a ton of maximum strength work for throwers - the event in track and field that assumedly requires the most absolute strength. Would you then argue that even less time be spent developing this ability with non-throwers? Frans Bosch argues that most athletes can easily attain “strong enough … and that it is pointless to invest in anything more”. What would Bondarchuk say to this statement - and would you agree?

EVELY

With some reservations, I would agree with Bosch. And so would Bondarchuk without reservation I believe. However, I don’t buy into the idea (as many do) that there is data out there that can tell you exactly what the level of absolute strength needs are for any given event. It’s fun to look at and offers some insight, but I believe the level of absolute strength needs for a given event is highly individual and to some degree a floating line from athlete to athlete. So to put all of your energy into chasing something that is so potentially ambiguous seems like a waste of time to me. I keep an eye on it, but do not let it directly dictate my training prescriptions. And yes, I think Bosch is correct in that whatever the level of strength is it is not all that hard to attain it, especially for gifted athletes.

JORDAN

This likely pushes the buttons of much of the North American strength and conditioning community and some of the strength scientists out there.

The answer to the question: “how much strength is enough” invariably is “there’s never enough!!”

Of course, I fall in Bosch’s camp - namely that it is one dimension of how an athlete expresses force, and while it transfers to rapid force production, it just doesn’t seem to be the case that top level coaches and athletes have adopted the philosophy espoused by those who say you can never be strong enough.

Derek - do you have any examples where an increase in strength did not transfer? I guess the flip-side is that if we never endeavored to push maximal strength to it’s absolute limit, we would never know if there was more hidden potential in an athlete. Of course alongside pushing maximum strength in the gym comes interference effects, risk for injury/MSK breakdown and just a lot of mental fatigue but maybe there is more to be gained. Unfortunately, my intuition just doesn’t line up with the the idea of there is no downside to continually getting stronger.

EVELY

Let’s say that we believe there is an absolute necessary level of strength and we have a fairly precise idea of what that is. Still to me, the more important question is not “do you need it?” or “what is that level?” but rather “how do you get it”.

I have seen simply far too much anecdotal evidence suggesting that lifting in the lower zones of the F-V curve produces the requisite (if not exceptional) gains in maximal strength. Look at Matt’s excellent table of loading parameters; I believe that most of those distinctions employing intensities above roughly 70% 1RM will produce enough gains in absolute strength for a given athlete over the long term, provided they are performed with the proper intensity / velocity.

JORDAN

I certainly appreciate this comment and of course, I wouldn’t have put it in there if I didn’t think it worked also. Again, we seem to have a disagreement with the purists out there who say there is no such thing as too much strength and the best way to get it is to lift heavy. They seem to feel that anything done below 85% 1RM is largely ineffective and athletes perform despite what they do - not because of what they do. On the flip-side, there are some nice papers that show that lifting to failure isn’t necessary to improve maximal strength. I also think that the Zone 1 and low end Zone 3 work is highly effective especially when we adjust density and volumes to provoke adaptation. I think this is something we should test somehow.

EVELY

Of course, if you are a powerlifter, over-reliance on sub-maximal intensities will just not work. But if you accept what I have written above regarding the employment of maximum strength loads, and their possible deleterious effects on specific workloads (not to mention Bondarchuk’s evidence that it doesn’t transfer as much as we think anyway) then coaches may ask themselves “why bother with it when I can attain it in an easier, safer way with better transfer?”

It is a question worth looking at.

JORDAN

This is certainly a different way of thinking compared to what I see going on in most gyms and in most circles in North America. However, get outside of North America and spend some time in other countries and it’s pretty clear this is exactly how it works. Again, I would say that the two big sources of maladaptation I have seen have been by doing too much Zone 3 lifting at the wrong times and with too much volume, and exercise/load mismatch (i.e. a mismatch between the athletes’ biological adaptive potential and the environmental changes). I am sort of stealing this from Daniel Lieberman’s new book The Story of the Human Body - he talks a lot about ‘mismatch disease’ - i.e. cultural evolution exceeds the biological evolutionary ability to adapt. I see a similar line of thinking fitting for athletes - where a coach or sport’s paradigm of choice is the ‘cultural evolution’ (an example of which on the cultural side might be food processing and an abundance of high-sugar foods) and the biological adaptive potential is the biological evolution (an example of which might be our hard programming to seek high calorie foods and remain sedentary to promote brain development and procreate). I just reframe the biological/cultural evolution with the athlete’s adaptive potential and what we prescribe based on the ‘training paradigms’ we concoct (sometimes without a lot of thought or good reason).

EVELY

The bottom line to me is that this is very much related to our discussion in regards to training organization; those who believe a certain amount of maximal strength is absolutely necessary to a) achieve a given performance and b) act as a ‘base’ for the development of other abilities, are going to naturally choose a staged-sequential form of methodology. Those who believe that the requisite levels of maximum strength can be achieved through specific workloads will most likely use a parallel-complex set up. To me, the latter makes more sense because it affords us to kill two birds with one stone: allowing for a larger, higher quality degree of specific work, while simultaneously developing the needed foundational strength levels. It may take longer to develop the desired strength levels, but the overall quantity and quality of specific work will be better, and the strength will transfer more efficiently because it is developed in harmony with the other specific forms of work.

When it comes to training I think like an economist so I choose this route.

So while it should be pretty obvious where I stand on this issue, I want to share an experience with you that may offer some insight when it comes to the danger of dogmatic thinking in the planning of training.

There is another reason for employing a maximum strength cycle that is rarely discussed (perhaps that is because I am foolish for suggesting it). I am talking here about employing such loads as a simple stimulus change.

I remind you of last year in May with Sultana Frizell. We had come to a point in her time with me where we were running out of options in terms of how to stimulate an adaptation response in her and I felt we needed to go a bit rogue. At 30 years old and after 8+ years of not having directly touched any maximal strength work I decided to cautiously introduce some into a maintenance cycle in the form of squats. My thinking was that rather than get a direct strength transfer effect from the experiment the change in stimulus was what was needed - a systemic ‘reboot’ of sorts. It was risky because she was throwing well at the time but I knew to improve further she needed change and this might be a way to get it.